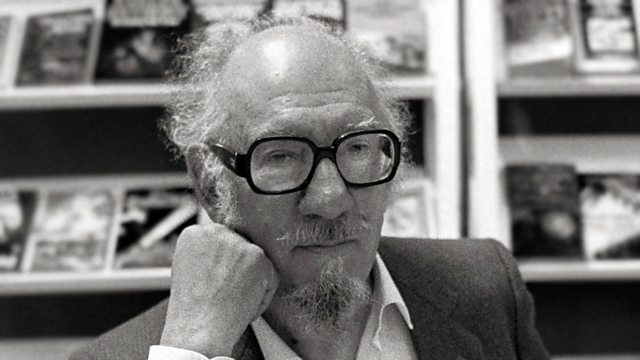

Julian Gustave Symons

- Born: 30 May 1912, London, UK

- Died: 23 November 1994, Kent, UK

Recommended works

- A Man Called Jones (1947)

- Bland Beginning (1949)

- The 31st of February (1950)

- The Man Who Killed Himself (1967)

- The Blackheath Poisonings (1978)

- Death’s Darkest Face (1990)

Overview

Julian Symons’s works are primarily anti-detective stories, closer to Kafka than Christie.

(Note: There are a handful of successful orthodox works – for instance, Bland Beginning and The Plot Against Roger Rider.)

Symons is concerned with power, irrationality, “the violence behind respectable faces” (in John M. Reilly, Twentieth-Century Crime and Mystery Writers. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1980), and the relation of the individual to an inhumane and uncaring society (Larry E. Grimes, “Julian Symons”, in Earl F. Bargainnier, Twelve Englishmen of Mystery, 1984).

Symons’s work is at once Absurdist, full of surreal imagery and symbols, and Naturalist, with suburban settings, sexual psychology, and realistic crime. The protagonist is often ineffectual or a miserable failure (Symons thought he was too fond of ‘weedy’ characters); his fantasies starkly contrast with the harshness of reality; and he either discovers or loses his identity.

For Symons’s admirers, such as Grimes, his work is comedy, “marked by a realistic treatment of character and scene, a coherent and consistent view of self and society, and a penetrating analysis of the relation of masks, dream, game and fantasy to life in a systematised, sanitised, urbanised world”.

To his detractors, Symons is Julian the Apostate, the man whose views on the superiority of the crime novel to the detective story have influenced almost every critic since.

From the detective story to the crime novel

Symons’ history of the genre (Bloody Murder, 1974) is teleological. The inferior detective story, an artificial puzzle without character or theme, developed into the superior crime novel, “a bag of literary all sorts ranging from comedy to tragedy, from realistic portraits of society to psychological investigation of an individual”.

The form began in the 19th century with Gaboriau and Fortuné du Boisgobey in France, Edgar Allan Poe in America, and Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens in Britain. The detective story reached its first peak with Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes in 1887. Doyle was followed in the Edwardian period by G.K. Chesterton, E.C. Bentley, and A.E.W. Mason, all of whom were good stylists.

Then came the Great War, and the detective story degenerated into an artificial puzzle, written by boring writers such as R. Austin Freeman or Freeman Wills Crofts, whom Symons dubbed the ‘Humdrums’. These writers were popular in the 1920s, and all was gloom and despair.

Even flashier writers like Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, and Ellery Queen were more concerned with plot construction and ingenuity than with realism, social commentary, or psychology. Because these writers were only interested in the problem, their books were artificial and trivial—in short, sub-literary.

The characteristic detective story has almost no literary merit, [but] may still be an ingenious, cunningly deceptive and finely constructed piece of work…

To abjure voluntarily the interplay of character and the force of passion was eventually to reduce this kind of detective story to the level of a crossword puzzle, which can be solved but not read, to cause satiety in the writers themselves, and to breed a rebellion which came sooner than has been acknowledged.

The only hope came from Anthony Berkeley (Cox). Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932), groundbreaking crime novels published as Francis Iles, would provide a model for future writers.

Some writers—Margery Allingham, Nicholas Blake, Ngaio Marsh, and Michael Innes—attempted to bring new life to the moribund genre by emphasising character, style and storytelling. Nevertheless, they were still concerned with plot, however humanised.

All they managed to do, as Wagner said of Rossini, was to give a corpse a semblance of life, making its ghastly cadaver bloom with roses, while worms and maggots devoured it.

The detective story was still dead.

The Golden Age was not the main highway of crime fiction that it looked at the time, but a minor road full of interesting twists and views which petered out in a dead end.

Instead of entertainments for tired businessmen and their wives, a new approach was needed that preserved the crime element but emphasised social commentary, psychology, politics, and philosophy.

Fortunately, WWII came along. The war exposed the detective story’s basic assumption that “human affairs are ruled by reason” and “crimes were committed by individuals, small holes torn in the fabric of society” as illusion.

Instead, writers realised that “a different world existed, one in which force was supreme and in which irrational doctrines ruled more than one nation”.

Reason, objectivity, and the search for truth had been exposed as shams.

The detective story was buried, and writers produced crime novels instead, in which there was far more emphasis on emotional states (chiefly angst and guilt), philosophy, and social commentary (ideally Existentialist or Marxist), and less of this tedious plotting and clueing. Hurrah!

To sum up: In the detective story, the problem is more important than or excludes characterisation, atmosphere or setting. It is politically conservative with no interest in a theme: “the detective and the puzzle are the only things that stay in the memory”.

In the crime novel, characters are more important than story; atmosphere and setting are emphasised; the attitude is often “radical in the sense of questioning some aspect of law, justice, or the way society is run”; and characters and situation are memorable.

Symons, Grimes argues, “effectively adapted crime literature to the purpose of radical social critique while pushing the genre into the realm of serious literature.” Does he, and, if so, is this a good thing? What effect did Symons’s reforms have on the genre?

Xavier Lechard suggests that, until Symons, the detective story was seen as tree bearing many different sorts of fruit. Critics might prefer Carr to Crofts, Hammett to Christie, but they nevertheless respected them, and were aware of their importance to the genre.

Symons’ effect on the detective story was the same as Wagner’s on opera: everything was judged by the standards of the Artwork of the Future, and those who had different aesthetic standards were banished from the artistic canon.

Under the influence of Symons’s triumphalist propaganda, the history of the detective story—an understanding of the development of the various schools, and the influence, for instance, of Freeman, Crofts, Bailey, and Mason on Christie, Carr, and Queen—was lost.

The wheel has turned, however. . The recent effort of critics like Mike Grost, Curtis Evans, and Martin Edwards suggests that the future of detective fiction criticism lies not in a “narrowing circle”, but in establishing the history of the genre, and in reestablishing reputations.

Absurdism

Perhaps Symons’s hostility to the genre comes from the fact that he was not a very good plotter; the plots are often cluttered and chaotic, or the solutions are arbitrary, which may reflect his belief that we live in a chaotic world.

Many of the endings are ambiguous. It is often unclear whether the detective has solved the mystery: either the evidence on which the detective bases his solution is wrong, or else equally tenable solutions are proposed without any indication which is the right one.

Finding out the truth can have disastrous consequences: the protagonist of The Criminal Comedy of the Contented Couple (1985) will be murdered by the people whom he accuses, while in The Blackheath Poisonings (1978), SPOILER the boy Paul is both detective and murderer: his investigations do harm, leading to his aunt Irene’s arrest; to secure her release, he poisons the murderer, which may represent the destructive role of the detective, who is not only a discoverer of truth but an executioner, inasmuch as Great Detectives bring guilty people to the gallows. The restoration of order that Symons perceives as a hallmark of the conventional detective story is either absent or subverted.

The classic example is The 31st of February (1950), in which the protagonist Anderson loses his faith in reason; order is represented by Inspector Chesse, who persecutes Anderson and drives him mad. The investigating policeman is menace, not saviour, and builds his seemingly logical case on a ‘clue’ that is ultimately misleading. It is, therefore, both an indictment of the detective story’s emphasis on reason, and a philosophical nightmare that examines the dissociation of identity, alienation, and failed attempts to impose meaning and order on a disordered and ultimately meaningless existence.

Nihilism recurs throughout Symons’s work. A young couple dream of owning a caravan but are ruined in The Narrowing Circle (1954) by a lack of free will and choice; the investigators in The Progress of a Crime (1960) are not concerned with justice and the search for truth, but either with making a case stick or creating a media story.

Realism and fantasy

Symons also believed that the crime novel had to become realistic to be literary (Grimes, 1984); for this reason, reality destroys imagination and fantasy.

Perhaps the supreme example is The Man Whose Dreams Came True (1968), a downbeat, depressing story, in which nasty things happen to the idealistic hero until he dies, no doubt an expression of the human condition.

Similarly, A Three Pipe Problem (1975) is not so much a Sherlock Holmes pastiche as a rebuttal of late nineteenth century Romanticism. Because Symons was philosophically opposed to Great Detectives, the actor playing Holmes who tries to use Holmes’s methods to solve a series of murders is a pathetic figure of fun; he solves the mystery, but more through inept bumbling than through genius. Symons subverts the grandeur and vitality of Doyle, presenting 1970s London as a drab and sordid place full of gangsters, prostitutes, lowlifes, and motor cars.

Works

- The Immaterial Murder Case (1945) ***

- A Man Called Jones (1947) ***

- Bland Beginning (1949) ***

- The 31st of February (1950) ****

- The Broken Penny (1953) **

- The Narrowing Circle (1954) **

- The Paper Chase (1956; also published as Bogue’s Fortune) ***

- The Colour of Murder (1957) ****

- The Gigantic Shadow (1958; also published as The Pipe Dream) **

- The Progress of a Crime (1960) *

- Murder! Murder! (1961; short stories)

- The Killing of Francie Lake (1962; also published as The Plain Man)

- The End of Solomon Grundy (1964)

- The Belting Inheritance (1965)

- Francis Quarles Investigates (1965; short stories)

- The Man Who Killed Himself (1967) ****

- The Man Whose Dreams Came True (1968) *

- The Man Who Lost His Wife (1970)

- The Players and the Game (1972) **

- The Plot Against Roger Rider (1973) ****

- A Three Pipe Problem (1975) *

- How to Trap a Crook (1977; short stories)

- The Blackheath Poisonings (1978) ****

- Sweet Adelaide (1980)

- The Great Detectives (1981)

- The Detling Murders (1982; also published as The Detling Secret)

- The Tigers of Subtopia (1982; short stories)

- The Name of Annabel Lee (1983)

- The Criminal Comedy of the Contented Couple (1985) **

- The Kentish Manor Murders (1988)

- Death’s Darkest Face (1990) *****

- Something Like a Love Affair (1992) *

- Playing Happy Families (1994)

- The Man Who Hated Television (1995; short stories) **

- A Sort of Virtue (1996)

- The Detections of Francis Quarles (2006; short stories)