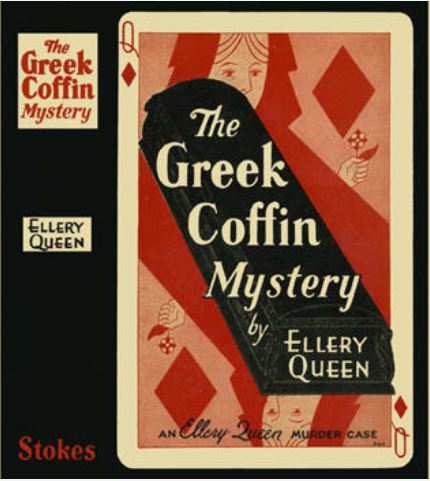

- By Ellery Queen

- First published: US: Frederick Stokes, 1932; UK: Gollancz, 1932

Period I Ellery Queen doesn’t get a lot of love these days. JJ at The Invisible Event struggled with The Roman Hat Mystery and The French Powder Mystery. The Green Capsule was underwhelmed by Roman Hat, French Powder, and The Tragedy of X.

You might almost call them “the national whatsit miseries”.

Guys, I feel your pain, and this one is for you.

I first read Greek Coffin nearly twenty years ago (1999, to be exact), and was impressed. I’ve since seen it praised to the skies by critics and bloggers alike. I got hold of most of Period I Queen a decade ago, and reread them – all except this one and Roman Hat. Coffin‘s inaccessibility made it seem even more special.

I built up a mental picture of Greek Coffin as the puzzle plot at its height: ingenious, subtle, and elaborate, with four (!) closely argued solutions. It rises above the mass of ordinary detective stories like a granite island erupting out of the sea, a monument to the colossal ingenuity of the Golden Age. There should be a full orchestra playing something epic – Shostakovitch or Prokofiev.

On one level, it’s a lesson in logic. This is Ellery’s first case; he’s straight out of college, and an insufferable know-all.

His first solution, based on the color of the dead man’s neckties and six cups of tea, is ingenious – but wrong, because it’s contradicted by two facts he didn’t know – and it doesn’t take all the known facts into consideration, either.

He feels so mortified that he vows: “Never again will I advance a solution of any case in which I may be interested until I have tenoned into the whole every single element of the crime, explained every particle of a loose end—”

Ellery has been led by the nose. X has laid subtle false clues to make him think wrongly. And Ellery learns from this. He makes mistakes, he learns how to think like his opponent, first to match, and then to beat him.

Greek Coffin keeps getting more and more intricate. It expands ever outwards, with false solution piled on false solution, while Ellery’s deductions become more involuted, a network of strands as delicate as a spider’s web.

Why, though, does it have to be so dull?

Yes, I acknowledge that it’s densely plotted and logical – but there’s damn all in the way of characterization, atmosphere, or humor. The multiple solutions are ingenious – but Anthony Berkeley‘s Poisoned Chocolates Case offers eight solutions (twice as many as Greek Coffin) – and it’s clever in a way that Queen’s laborious, elephantine effort isn’t.

Ellery calls the murderer’s scheme “a complex plan which requires assiduous concentration for complete comprehension”. Complex? To quote Andy Dalziel, “it’s f–ing contortuplicated”. Trying to keep track of all the subtle deductions and inferences is mentally exhausting – not for the faint of brain. My own organ had glazed over. So had my brain.

And Ellery’s explanation – which in most editions runs to more than 30 pages of closely printed type – is tedious. Ellery gives us a long-winded lecture in applied logic.

The Green Capsule beautifully describes the typical Period I methodology:

“Given facts A, B, and C, we can deduce D. But, since we know that B isn’t true, we must subdivide by F thereby imply G. Add G to A and C, and, gentleman, we are only left with one possible conclusion – H.”

Queen comes closer than most writers to Freeman‘s definition of the ideal detective story reader as “men of a subtle type of mind”: “theologians, scholars, lawyers, and to a lesser extent, perhaps, doctors and men of science” – readers who are interested in a logical argument, “in which the matter to be proved is usually of less consideration than the method of proving it”. What matters is the proof, not the solution.

And Queen gives us plenty of proof, till we’re drowning in the stuff. Ellery builds up chain upon chain of logical deduction, to the point where I was reduced to writing them down to keep track of his reasoning. It’s logic, logic, and more logic, like the Sudoku from hell.

Think about it this way. Queen is often considered one of the masters of the fair play puzzle plot, with John Dickson Carr and Agatha Christie – but Queen is a drier writer. Carr was a natural storyteller, who saw the detective story as a branch of the story of adventure and imagination; he was no more capable of writing a dull page than Leslie Charteris was. Christie is witty, “the mistress of simplicity”, as Robert Barnard called her.

Queen may be more thorough, more intellectually rigorous, but he lacks Carr’s vigor or Christie’s deceptive lightness.

Carr and Christie, like Chesterton, create situations that seem complex – how do all these clues and characters fit together? How does this situation even make sense? – and then, as G. K. C. said, illumination.

“The object [of a mystery] is not darkness, but light; light in the form of lightning” or “the breaking of a dawn”. Their solutions can be written in one sentence, and make sense of everything.

Queen’s, though, is complex, and, on one level, arbitrary. Let me put it as delicately as I can, without spoiling anything. I remembered who did it – wrongly. I remembered the function they played in the story, not the name. There are logical reasons why X could have done it, and not B – but the authors could have reversed those conditions, and not needed to change a single thing about their personalities. Characterization is irrelevant.

There’s little in the way of situational or character-based clues – no tightening of hands on window-sills, or dropped spoons. There’s one passage where X looks at Ellery in a significant way; otherwise… This isn’t like a Carr or Christie novel, where conversations and actions suddenly take on new meaning, and you kick yourself mentally for missing their real significance.

Instead, the clues are material (physical) clues – typewriters, bank-notes – from which Ellery deduces. Queen, at least in the early books, wasn’t much interested in people. Even in later books, when they’re trying to introduce human interest and serious themes, the clues are unrelated to human nature.

Take The Siamese Twin Mystery (1933), in which half a dozen people are isolated by forest fire, in an increasing state of nervous and moral tension. Agatha Christie (And Then There Were None, 1939) and Ngaio Marsh (Death and the Dancing Footman, 1941) also wrote books about characters trapped in a location, but concentrated on their characters’ psychology and relations. Here, the detection relies on torn playing-cards clutched in the victims’ hands, and left handed and right-handedness. The Origin of Evil (1951) is ‘about’ Darwinian evolution and the survival of the fittest, but the principal clue is SPOILER the absence of the letter ‘T’ in a letter.

Queen’s logic is also faulty. He’s wrong about color blindness, for a start; sufferers don’t think red and green are different colors with reversed names; they can’t distinguish the colors, so red and green look the same to them. I’d also like a map of the second death scene, so I can visualize the head in relation to the bullet’s trajectory and the door.

Notes

- Mike Grost places Queen in the Van Dine school; there’s no doubt that Van Dine influenced the early books (except V.D. is more fun), but Queen is really closer to such British writers as Ronald Knox, with his bloodless, abstract exercises in logic.

- John Dickson Carr’s “Crime in Nobody’s Room” also involves color blindness (accurate!) and a forged / fraudulent picture.

Blurb (US)

Are you an Ellery Queen fan? If you are, The Greek Coffin Mystery needs no stronger recommendation than that it is Ellery Queen’s latest detective story.

If you are not, we envy you this opportunity of becoming acquainted with the foremost detective-story writer of our generation.

In The Greek Coffin Mystery – fourth of the series which has been confounding the armchair detectives of two continents – Ellery Queen presents a deductive problem stranger, more intricate, more mystifying than his own best-selling detective novel of last season, The Dutch Shoe Mystery…by comparison making the surprise and mystery elements of even that “masterpiece” (as the Philadelphia Ledger called it) seem as simple as a child’s picture-puzzle.

A tall order? Unquestionably. But Ellery Queen specializes in tall orders. He has set a standard for the modern analytical detective story which has brought him such press encomiums as “Ellery Queen is the logical successor to Sherlock Holmes,” and “Queen puts Sherlock away back in the shade.”

The story of The Greek Coffin Mystery revolves about the natural death of blind Georg Khalkis, internationally known dealer in objets d’art. Provocative circumstances lead to a disinterment of his corpse, buried in the old graveyard of one of New York’s midtown churches. When the coffin is opened…

No, gentle reader, your first guess is wrong. And this extraordinary discovery is merely the beginning of as dramatic and puzzling a chain of events as has ever tickled the brains of mystery fans…a story which further reveals Ellery Queen as the most human as well as the most brilliant of our “infallible” fiction detectives.

Contemporary reviews

F.P.A., New York Herald Tribune: Had me baffled but fascinated.

Isaac Anderson, New York Times: He knows how to write a first rate detective story.

Times Literary Supplement (30th June 1932): Ellery Queen, the pseudonymous author and detective hero of this book, is already known to English readers from the Roman Hat Mystery. The events treated in the present novel are supposed to take place at an early period of his career and to represent his first experience as a more or less amateur detective. The problem offered for solution here is difficult to solve, the red herrings are plentiful and the reasoning whereby the mystery is finally unravelled is close and the incidents exciting. The English reader usually finds an initial difficulty in American detective fiction from his unfamiliarity with the manners and customs of the inhabitants of the United States therein presented. Here we are not spared the violence and brutality of language which American writers apparently desire that we should recognise as natural to the American police. And, in addition, Mr. Ellery Queen is a somewhat irritating person. Whether he is reproducing his own conversation or is proceeding with the course of his narrative, he uses a pretentious jargon which must have annoyed his collaborators as much as it vexes his readers, and needs a dictionary in itself. Lastly, the method whereby the villain disposes of his victim’s body seems to require an incredible degree of physical strength. Yet anyone who can tolerate these peculiarities will find it difficult to put the book down until he has discovered who did the deed.

I’m with the Times reviewer that [early] Ellery is irritating, but I don’t remember the cops showing any particular “violence and brutality of language”! I think Greek Coffin is about as complex as a mystery can get without becoming just plain annoying to the reader, and it may well have crossed that line for other readers… the Queen team wrote other complicated solutions, but after 1932, they never again got quite this intricate.

Also. great point about how even later Queen is more about the physical clues than the psychological ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

The “police brutality” is probably British sensitivity – although Sgt. Velie is fairly Neanderthalesque!

Yeah, I think they pushed intricate plotting, as you say, as far as it could go. EGYPTIAN CROSS, their next, feels looser.

Have you read the short story “The African Traveller”? It has several multiple solutions all in a few pages – beautifully plotted, and clever.

LikeLike

Yes, I’ve read all of Queen. Many of the stories in The Adventures of Ellery Queen have enough plot and deductions to serve a whole novel, and The African Traveller is a great example.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see you made the same point about the Adventures in your reply to thegreencapsule. Seconding your endorsement of the New Adventures and Calendar of Crime. Each of the three collections has a weak story or two… well, more than one or two in the New Adventures… but most of them are gems.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Aaargh!!! I just finished trudging through The Dutch Shoe Mystery yesterday (review pending). I was elated. I finally made it to The Greek Coffin Mystery after suffering through the tedium of the first three Queen books and The Tragedy of X. Green pastures lay ahead of me.

The worst part is that I know deep inside that your review is going to be spot on. I was questioning things myself while I read The Dutch Shoe Mystery. “How do these books suddenly become interesting?” I found myself wondering. Well, four solutions would liven things up a bit, but I suspect they’ll still be wrapped in a dry husk of a story.

Oh well, I’ll find out for myself soon enough, I suppose…

LikeLike

Good luck with that!

Queen started to introduce more human interest towards the end of Period I, not always successfully. I’ve mentioned SIAMESE TWIN. .AMERICAN GUN is lively, and has a Chestertonian Surprise! solution; on the other hand, it has some cardboard characters, a plateau in the middle, and some readers think the method is impossible to swallow. SPANISH CAPE is better written and characterized, but you should be able to spot X without too much difficulty – and Patrick at The Scene of the Crime blog doesn’t like it much: http://at-scene-of-crime.blogspot.com.au/2012/05/mr-queen-on-essence-of-boredom.html. And that’s the last book of Period One!

THE DOOR BETWEEN and THE FOUR OF HEARTS, from Period 2, might be what you’re after in terms of lively detection + some character interest & atmosphere + clever plot.

The Period Three books are more experimental. Some have lots of character interest; CALAMITY TOWN is their most naturalistic work. A lot of the other books from the period go haywire – and, to give him credit, the Queen cousin who wrote the books (rather than the one who plotted) thought the plots he had to clothe in flesh and prose were outlandish and untrue to human nature.

The Period One book I’d really recommend isn’t a novel at all, it’s a collection of short stories: THE ADVENTURES OF ELLERY QUEEN. These have the high-powered ingenuity, double-facing clues, logical deductions, and tricky solutions of the novels – in about 15 pages each. It’s one of the all-time great short story collections. The cousins were really best at short stories; THE NEW ADVENTURES (which also has “The Lamp of God”, an impossible story about a vanishing house) and CALENDAR OF CRIME are also first-rate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seen quite a few comments that The Four of Hearts is rubbish, although I noted that you call it out as a strong read in your list of recommendations. I get the sense that this is from a period where the authors were writing with their sights set on Hollywood.

I’m curious to experience the change in writing and plot structure over the periods. In fact, I’m relieved to know that there are “periods” because that suggests a big shift from the style that I’m currently reading.

I’m definitely looking forward to the short story collections (I almost started one two weeks ago). The Adventures of Ellery Queen seems to be a popular book with everyone and luckily I have a copy, along with the other two collections you mentioned. I can see how Queen would work well in short story form. The overall writing is perfectly fine, it’s just that nothing of real interest happens in the novels between the introduction of the crime and the reveal of the solution. Chop them down to the length of a short story and I’d have no complaints.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For my money, The Four of Hearts is the strongest Period Two novel and one of Queen’s most enjoyable overall.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad to see someone else likes it; it’s got a mixed rep.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh dear. I am currently reading The Dutch Shoe Mystery so this would be my next one. I will brace myself accordingly!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whiskey’s always a good bracer!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to your review and the chance to compare notes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It will be interesting. I am looking forward to going back and taking a closer look at your review when I am done and will know the parts of the book you are talking about!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another one I read about 1979. Rereading it was a catastrophe. Dull, dull, dull and (perhaps for that reason) the reasoning looked silly. I really liked EQ period 1, much more than the later stuff, when I first read it.

I hope French Powder and the stories hold up better than this one … 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love your review, although I do love early Queen myself. I recognize and agree with every fault you levied against the book and Queen at large, but the only difference is that I find these Sudokus from Hell very amusing and fun indeed.

My only note, though, is that the “color blindness” isn’t quite faulty logic so much as it is Queen using the wrong term for a totally different phenomenon. The only stutter I recall in that section is the misuse of the term, but that the rest still stands otherwise.

LikeLike