- By R.C. Woodthorpe

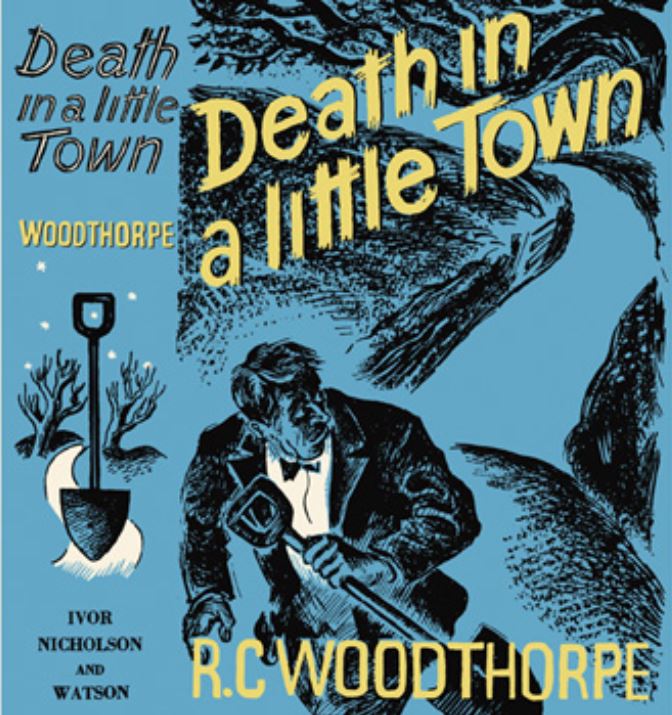

- First published: UK: Ivor Nicholson and Watson, 1935; US: Doubleday, 1935

- Availability: Resurrected Press, 2015

R.C. (Ralph Carter) Woodthorpe (1886–1971) was a minor writer of the Golden Age, whose eight books were positively reviewed by Dorothy L. Sayers, Nicholas Blake, Isaac Anderson, Will Cuppy, and later Barzun and Taylor.

Mr. Woodthorpe is one of the very few detective writers in the course of whose work the reader can forget that a crime has been committed and imagine himself in the middle of an entrancing novel of manners… Mr. Woodthorpe must be a godsend to those die-hards who dare not be discovered reading anything that is not literature, and who yet like a detective story.

Torquemada in The Observer

But Death in a Little Town suggests Woodthorpe’s strength was the novel of manners, not the detective story. True, The Times Literary Supplement considered it “both good comedy and good detective fiction” – the story was admirably managed, and the writing excellent; and Milward Kennedy (The Guardian) admired Woodthorpe’s “skill in providing a comedy of character and manners without distracting the reader from his desire to solve the riddle“. But Ralph Partridge (New Statesman) thought “the background of provincial society in Sussex is really more congenial to his gift as a novelist; the crime is only an incident in the cross-currents of local gossip and intrigue”. The Saturday Review of Literature objected that the sleuthing was “almost invisible to the eye”; Mike Grost considers the mystery and detective aspects tenth-rate; and Barzun and Taylor were not impressed:

Not up to this author’s best. The village setting and characters are poor-grade Christie, the detective is given little chance to shine, and the plot works itself out without help from the author. Cattiness prevails and provides some amusing conversation at a tea party.

Little Town introduces Woodthorpe’s series character: hook-nosed, moustached, belligerent spinster Matilda Perks. (“I am crafty and sour and vindictive.”) It would be too much to call her a detective; she sees the murder done, and conceals her knowledge, because she loathed the victim and liked the killer.

Douglas Bonar, an unpopular landowner, blocks the traditional right-of-way across his fields; the villagers tear down the barrier, and he stumps off to call the police. That night, novelist Michael Holt finds Bonar dead in the middle of the street – brained with Holt’s own spade. Worse, Bonar had given Holt a 24-hour ultimatum before he exposed his secret. Fearing he will be suspected, Holt cleans the spade of the blood. When he returns, Bonar’s body has disappeared; it is found the next morning, in the river.

As critics have found, the writing and characterisation satisfy more than the mystery. Who did it gradually emerges before the end – not through clues, but through Woodthorpe’s focus on character and through others’ attitudes towards the culprit. The crime, moreover, is manslaughter, which is almost always an anticlimax. (The US edition let readers down gently; the blurb announces it is “Inadvertent murder”.)

But the people are extremely well done. The characters’ marital and romantic problems are more nuanced than one would expect from a minor writer. Holt, 17 years later, meets the girl he once loved as a chivalrous, foolish 21-year-old. Pompous, fussy Chrystal is odious but convincing, a detestable little man who gives his wife a black eye and bullies her. Thornhill met Bonar’s niece – an efficient headmistress – on a Mediterranean cruise, and is engaged to her; will their relationship survive the strain of murder? Thornhill is the most alive character in the book; his language is Falstaffian in its vigour and exuberance: “You would think it impossible for him to shrink, since he was already a homunculus, a pygmy, a mannikin, a duodecimo, a wraith, an ambulant skeleton: yet I could swear that he has lost flesh. From him that had not has been taken even that which he had. He will soon be an impalpable presence.”

Would one actually want to live in a little town or an English village? Chesworth seems a pretty ghastly place: hidebound and insular, full of gossips, bores, and religious conservatives who think cinemas and sport on Sundays profane the Sabbath. Did you know you couldn’t see a play on a Sunday in Britain until the 1970s? Instead, one was meant to be miserably devout. Frankly, reading 1930s English detective fiction makes me glad to live in the 21st century. Sure, we can’t swim or see a play or a movie at the moment (I’m in my ninth week of lockdown), but that’s because of COVID, not puritans. Like Thornhill, I’d be tempted to set up a nudist colony. As it is, hurrah for streaming.

Blurbs

1935 Ivor Nicholson and Watson

No writer of crime stories to-day has been more enthusiastically acclaimed by discriminating opinion than Mr. R. C. Woodthorpe. His Public School Murder was the outstanding success of its season in this department of fiction, and his Dagger in Fleet Street was described by Miss Dorothy L. Sayers as “dazzling and delicately cynical comedy, a glad gift to a dull world.”

In his new novel he sets his scene in a small Sussex town, and constructs an ingenious and baffling problem around the death of a recalcitrant landowner during the townsmen’s attempts to enforce an ancient right-of-way through his property.

The story is told with Mr. Woodthorpe’s customary [ILLEGIBLE] and distinction of style, and its background of typical small-town life provides a congenial subject for his gently ironical wit.

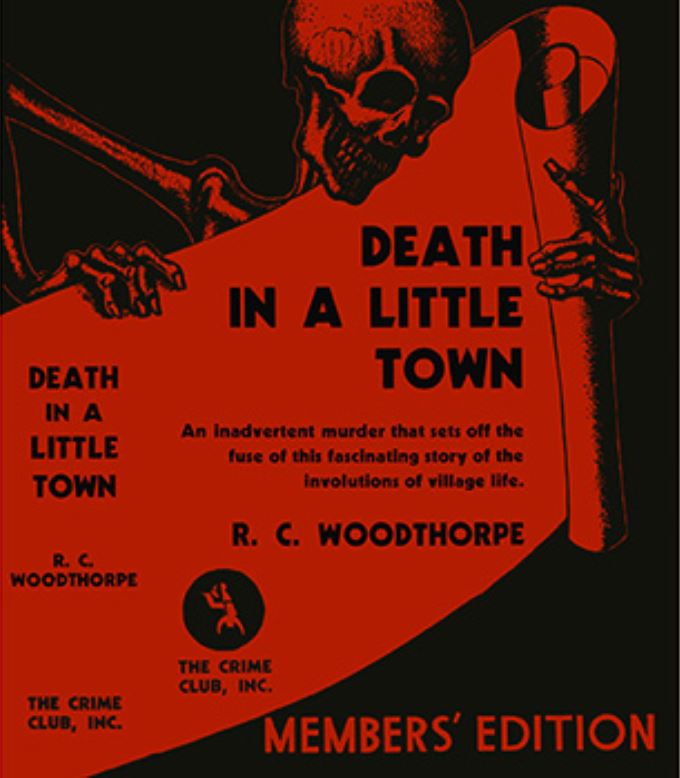

1935 Doubleday (USA)

INADVERTENT MURDER

Murder, an inadvertent murder in a quiet little English town sets off the fuse of this fascinating story of the involutions of village life.

The elderly spinster, Miss Mathilde Perks, with the crotchety tongue; Robert Perks, with his “queer spells” which caused him to undress casually wherever he was; Miss Perks’ amazing parot, Ramsey MacDonald, with his amusing talent for speaking unpleasant truths; Walter Chrystal, that boresome and suspicious little husband; and his wife Daphne, a slattern and a supreme fatalist; Frank Thornhill, a man who had devoted the earlier years of his life to winning silver cups on the field of sport, and now in middle life was devoting himself just as earnestly to the emptying of silver goblets, are all whirled into the maelstrom of the crime. Humour, drama, a touch of tragedy combine to make this a vivid and amusing story of a genuinely hated man.

Contemporary reviews

Observer (Torquemada, 20th January 1935): Mr. Woodthorpe is one of the very few detective writers in the course of whose work the reader can forget that a crime has been committed and imagine himself in the middle of an entrancing novel of manners. If there is a left edge to this blade of compliment, it is blunt and of no importance. As in Dagger in Fleet Street and Silence of a Purple Shirt, Mr. Woodthorpe does not leave himself space, in the midst of his delightful character drawing, to give us more than a few-piece jigsaw; but again the shapes are queer and hard to put together. Our heart sank when we discovered that our heroine was to be a bluff old lady with a blunt tongue; but Miss Perks turns out to be very different from Miss Legion, and we part from her with that sudden sorrow in which we part from living friends. Mr. Woodthorpe must be a godsend to those die-hards who dare not be discovered reading anything that is not literature, and who yet like a detective story.

New Statesman & Nation (Ralph Partridge, 26th January 1935): When the unpopular nouveau riche owner of Chesworth Park was chopped dead with a spade the night the Chesworth citizens chose to enforce their right of way across the Park, there were plenty of people who had the opportunity and the inclination for such drastic action. Which of them actually wielded the spade is the problem set by Mr. Woodthorpe in Death In A Little Town, but the background of provincial society in Sussex is really more congenial to his gift as a novelist; the crime is only an incident in the cross-currents of local gossip and intrigue, which he notes down with such malicious gusto.

The Guardian (Milward Kennedy, 29 January 1935): Death in a Little Town is another example of the value of motive in an investigation of murder. That the rich Mr. Bonar had been murdered was a thing which no one resented. That Michael Holt, murderer or no, had been menaced by Mr. Bonar, that he had been one of a working party engaged in preserving a right of way across Mr. Bonar’s land, that he had found the corpse with his own blood-stained spade beside it – all this and more besides caused him grave anxiety and led him into lies; and jealous Mr. Chrystal, in whose keeping the spade had been before the murder, and the Unknown who flung the corpse into the river, and old Miss Perks, who was out that night looking for her attractive but demented brother and whose brooch– But such a catalogue suggests, wrongly, that the plot is complicated rather than subtle; nor does it hint at the particular attraction of the story, which is its skill in providing a comedy of character and manners without distracting the reader from his desire to solve the riddle. Often the humour is a Tartare sauce; in one scene I thought that there was too much of it, but I confess that the end proved me mistaken. Let us hope that we shall hear more at any rate of Miss Perks, with her delight in unpleasant truths and her unshaken determination to have a heart of dross.

Times Literary Supplement (14th February 1935): Someone killed Bonar, the village tyrant, by hitting him on the head with a spade. It might have been Miss Perks’s half-witted brother, Robert; or Chrystal, who suspected Bonar of an intrigue with his wife; or Holt, over whose head Bonar was holding the threat of disclosing a secret of his early life. Circumstances pointed to Holt, for his spade did the business, he had the opportunity and the strongest motive. Miss Perks knew who did it, but she kept the knowledge to herself, meaning perhaps to disclose it if the police arrested the wrong man. The story is admirably managed. The writing is excellent. And, though each character has sufficient oddity to suggest caricature, those who live in such a small town as Chesworth have their own oddities for those who can see them. This is both good comedy and good detective fiction.

Boston Transcript (8th June 1935, 330w): As the search progresses you are assured of many delightful insights into the involutions of the life in Chesworth as well as enjoying to the fullest the interesting and amazing characters Mr. Woodthorpe introduces into this clever and unusual baffler.

Sat R of Lit (8th June 1935, 30w): Bucolic British atmosphere and character work—fine: sleuthing—almost invisible to eye.

Books (Will Cuppy, 9th June 1935, 160w)

NY Times (Isaac Anderson, 9th June 1935, 310w)

Springfield Republican (6th October 1935, 160w)

A Catalogue of Crime (Barzun & Taylor, 1989): Not up to this author’s best. The village setting and characters are poor-grade Christie, the detective is given little chance to shine, and the plot works itself out without help from the author. Cattiness prevails and provides some amusing conversation at a tea party.

Other blogs:

I have just acquired an R C Woodthorpe book, The Necessary Corpse but I’ve never read anything else by him. The quotation from Torquemada sounds like Woodthorpe is just up my alley. After reading a lot of fiction I find the simple ability to create interesting people whom I enjoy spending time with is probably the single most vital asset a writer can possess. Sounds like R C had at least mastered that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hmm – reviews of that one are mixed.

E..R. Punshon, Manchester Guardian (28th March 1939): An odd and somewhat disconcerting mixture of farce and melodrama.

Isaac Anderson, NY Times (11th June 1939):

There is very little mystery, so far as the reader is concerned, but there are complications and unexpected developments enough to keep one’s interest alive until the final page. There is real enjoyment in store for the reader of this book.

New Yorker (17th June 1939): The really humorous writing disguises a pretty wild plot.

Will Cuppy, Books (18th June 1939):

We’re not saying that The Necessary Corpse is any great masterpiece, but it’s well above the average and an ideal mystery for the hot spell.

Barzun & Taylor, A Catalogue of Crime (1989):

Hard to classify: the author is no amateur but his aim here is diffuse and he seems to have no control over his story. The “humour” grows and grows at the expense of credibility and sense.

LikeLike

I have now finished reading THE NECESSARY CORPSE and agree with Isaac Anderson. I enjoyed the story but it is a comedic farce and a Wodehousian romp and not truly a mystery.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was recommended to me about two years ago, and I’ve yet to track it down…but you’ve convinced me that such an outcome may be a most desirable one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hope you enjoy it!

LikeLike

I can remember the days when you couldn’t go to a pub on Sundays in Australia. In fact you couldn’t do anything much other than go to church. The shops were closed as well.

Personally I find that one of the attractions of golden age detective fiction is the opportunity to make a brief visit to a different world. But I’m inclined to agree with you – it’s not necessarily a world I’d want to live in.

As for Woodthorpe, I’ll probably give him a miss. I like detectives who do actual detecting.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And regional Australia can still be very quiet on Sundays! Still, at least cinemas were open, and there was no law against sport.

LikeLike