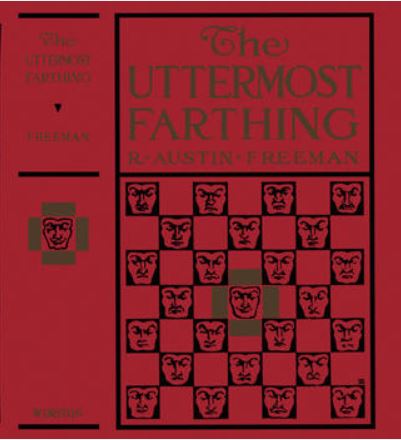

- By R. Austin Freeman

- First published: US: Winston, 1914; UK: Pearson, 1920, as A Savant’s Vendetta

The Uttermost Farthing is not one of Freeman’s most popular books. Hodder & Stoughton, his normal British publishers, refused to print it, claiming it was a “horrible book”; while Oliver Mayo (R. Austin Freeman: The Anthropologist at Large, 1980)’s appraisal is largely negative.

I thought it was hilarious. Whether you‘ll find it funny, I can’t guarantee.

It’s the story of Professor Challoner, whose wife is killed by a burglar, so he devotes his life to hunting crooks.

And by “hunting”, I mean murdering them, and displaying their heads as trophies in his private museum.

The main hall of his museum displays the usual specimens: whale skeletons, porcupines with ankylosed knee joints, camels with rickets, and aurochs with bone tumors.

And a sinister cabinet of human skeletons.

A secret chamber holds the Professor’s prize collection: Series B (“dry, reduced preparations”) – better known as the severed heads of burglars, shrunken in the Mundurucú way.

Professor Challoner is a follower of Cesare Lombroso, the Italian criminologist who believed that you could spot malefactors by the shape of their ears. (Ladri senza lobi.) G.K. Chesterton, in passing, abhorred Lombroso’s theories, which he saw as inhuman, denying free will, and overlooking the criminal’s capacity for redemption and salvation.

Criminals, Lombroso believed, are degenerates. And the Professor agrees.

“Criminals are vermin. They have the typical characters of vermin: unproductive activity combined with disproportionate destructiveness. Just as a rat will gnaw his way through a Holbein panel, or shred up the Vatican Codex to make a nest, so the professional criminal will melt down priceless mediaeval plate to sell in lumps for a few shillings. The analogy is perfect.”

Society, on the other hand, treats criminals far too softly.

The attitude of society towards the criminal appears to be that of a community of stark lunatics. In effect, society addresses the professional criminal somewhat thus:

“You wish to practice crime as a profession, to gain livelihood by appropriating – by violence or otherwise – the earnings of honest and industrious men. Very well, you may do so on certain conditions. If you are skilful and cautious you will not be molested. You may occasion danger, annoyance and great loss to honest men with very little danger to yourself unless you are clumsy and incautious; in which case you may be captured. If you are, we shall take possession of your person and detain you for so many months or years. During that time you will inhabit quarters better than you are accustomed to; your sleeping-room will be kept comfortably warm in all weathers; you will be provided with clothing better than you usually wear; you will have a sufficiency of excellent food; expensive officials will be paid to take charge of you; selected medical men will be retained to attend to your health; a chaplain (of your own persuasion) will minister to your spiritual needs and a librarian will supply you with books. And all this will be paid for by the industrious men whom you live by robbing. In short, from the moment that you adopt crime as a profession, we shall pay all your expenses, whether you are in prison or at large.” Such is the attitude of society; and I repeat it is that of a community of madmen.

It is, therefore, his duty as a public-spirited citizen to find the man who killed his wife and eliminate him.

He knows that his quarry has ringed hair, and left his finger-prints on the polished surfaces of the household plate. (How typically Freeman!) Finding him, though, isn’t so easy.

“It was very disappointing,” says the Professor, looking at his first victim’s unringed hair through his microscope. “I really need not have killed him, though under the circumstances there was nothing to regret on that score. He would not have died in vain. Alive, he was merely a nuisance and a danger to the community, whereas in the form of museum preparations he might be of considerable public utility.”

Like any good scientist faced with the problem of disposing of a corpse, the Professor does what any rational man would do: start an anatomical collection of criminal anthropology. What a fine way of studying degeneracy, he thinks.

Freeman’s deadpan account of how the Professor establishes, and adds to his collection is brilliant black comedy.

“I invite the criminal to walk into my parlor. He walks in, a public nuisance and a public danger, and he emerges in the form of a museum preparation of permanent educational value.

“Thus I reflected and mapped out my course of action as I worked at what I may call the foundation specimen of my collection. The latter kept me busy for many days, but I was very pleased with the result when it was finished. The bones were of a good color and texture, the fracture of the skull, when carefully joined with fish-glue, was quite invisible, and, as to the little dried preparation of the head, it was entirely beyond my expectations. Comparing it with the photographs taken after death, I was delighted to find that the facial characters and even the expression were almost perfectly retained.”

It’s that mention of “fish-glue” that does it, I think. Small boys have model aeroplanes, the Professor has human heads. It’s that dispassionate, practical tone when applied to murder that makes it so funny.

Another victim would, he believes, make a most interesting companion preparation to Number Five.

“Your Cousin Bill,” I said, with this new idea in my mind. “Was he the son of your mother’s sister?” (A few details as to heredity add materially to the value and instructiveness of a specimen.)

On one occasion, the Professor – now operating out of an East End barber’s shop – is confronted with the logistics of transporting corpses back to his home.

The centre of gravity of a cask filled with homogeneous matter coincides with the geometrical centre. But in a cask containing a deceased Jew, the centre of gravity would be markedly ex-centric.

As always, Freeman is full of ingenious ideas about crime; the Guy Fawkes plot is one to remember.

Several of his specimens, he notes with satisfaction, confirm to Lombroso’s types. One, for instance, presents “the ‘orthodox stigmata of degeneration’. His hair was bushy, his face strikingly symmetrical, and his ears were like a pair of Lombroso’s selected examples; outstanding, with enormous Darwinian tubercles and almost devoid of lobules.”

Lombroso’s theories, though, lead the Professor astray. Towards the novel’s end, the Professor knows that his quarry must be one of two men. One of them conforms beautifully to the Lombrosoan image of the criminal, so Challoner concludes it must be he. The Professor is mistaken; the other is the man. So much for Lombroso, then!

Some critics, such as Mayo, argue that we’re meant to sympathize and agree with Challoner – mistakenly, in my belief.

Professor Challoner gradually loses his humanity. Just as Lombroso reduces criminals to criminal types, the Professor reduces them to museum specimens.

“I watched him as well as I could through the chink of the cupboard doors by the dim light of the stinking paraffin lamp: a greasy, unwholesome-looking wretch, sallow, pallid and unshorn; and thought how striking he would look in the form of a reduced, dry preparation.”

The passage is at once hilarious and disturbing. The Professor no longer sees burglars as humans, and, in so doing, he has lost his own humanity.

The ending is as bleak as that of Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, another tale of murderous revenge and barber-shops.

When Challoner finally catches his wife’s murderer, it’s an anti-climax. He’s spent 20 years of his life, and grown old, seeking revenge – and that revenge is unsatisfying. The desire for revenge has cost him his happiness – and, Chesterton would say, his soul.

We’re left with the feeling that – however logical his arguments about the elimination of the burglar from society may seem – rationality without compassion or empathy has unmanned him.

Contemporary reviews

NY Times (12th April 1914, 60w)

Pub W (M.K. Reely, 18th April 1914, 600w)

Boston Transcript (29th April 1914, 250w): A story of sensational distinction, but nobody should read it unless he is prepared for a recital of horrors.

A Catalogue of Crime (Barzun & Taylor, 1989): Certainly a story of crime, with a bit of detection at the beginning and a great deal of circumstantiality throughout. It is remarkable how Freeman manages to give variety to a series of episodes fundamentally alike and to make us accept the melodramatic conception of the whole. The title is from Matthew 5:26.

As someone who has yet to read any Freeman, I may not start here! It sounds amazingly compelling in an experimental sort of way, but perhaps not the ideal opening salvo for a long-held love affair with a classic author. Thanks for bringing this up, though, because my desire to track it down at some point will accelerate my actually reading some of this Thorndyke stories in the coming year (or, ahem, thereabouts…).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I think you’ll enjoy the Thorndyke stories – but THE UTTERMOST FARTHING, intriguing as it is, probably isn’t the best Freeman to start with. Try THE EYE OF OSIRIS or AS A THIEF IN THE NIGHT.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much appreciated, thanks!

LikeLike

I had been aware of this title without knowing what it was actually about, but, admittedly, it does sounds intriguing! A complete and utter departure from his Dr. Thorndyke novels or even his Romney Pringle short stories. Something like a very early predecessor of modern series like Death Note (anime) and Dexter (TV-series).

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is intriguing. There are Thorndykean elements – Challoner, like Dr. T., is a brilliant old polymath who uses microscopes, fingerprints, and anatomy to track down burglars.

In one respect, it’s also a spoof of Conan Doyle. Professor Challoner — Professor Challenger. The narrator of the story is Dr. Wharton. And one of the book’s themes is evolution, degeneration, and atavism – see “The Crooked Man” or THE LOST WORLD, where Challenger looks like the Missing Link.

LikeLike