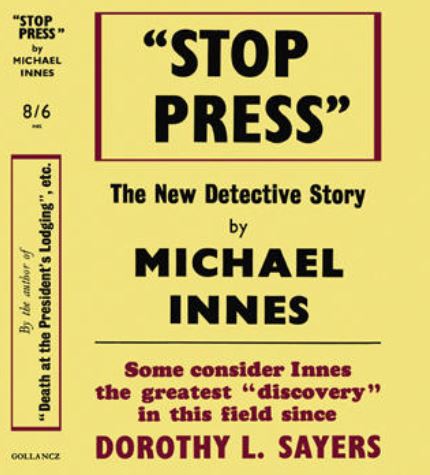

- By Michael Innes

- First published: UK: Gollancz, 1939; US: Dodd Mead, 1939, as The Spider Strikes

Michael Innes was the finest stylist in the genre since G.K. Chesterton; he is its Mervyn Peake in his Baroque imagination, the lightness of his fancy, and the density and precision of his language. Most detective fiction prose is functional, or (more charitably) transparent; one savours, one lingers over Innes.

Stop Press, Innes’s fourth novel, is a jeu d’esprit in the line of Thomas Love Peacock or early Aldous Huxley. It is a straight novel of a fantastical, literary kind (perhaps a semi-criminous cousin to Nightmare Abbey or Crome Yellow) – its resemblance heightened by the Penguin edition, which lends it the respectability and the cachet of the Great Tradition. (Take it or Leavite, one might say.)

But there is (let us warn the reader) no murder, and the problem is abstract: a fictional character has apparently come to life to persecute his creator. Instead of violent death, Innes provides witty characterization, literary allusion, and metaphysical badinage. Its closest antecedent is perhaps Sayers’s Gaudy Night, a murderless comedy of manners; there, however, the anonymous letters give form and definition. Innes amuses himself, creating denizens, painting scenes, and showing his characters at talk and tea.

“The Spider”, a criminal turned Robin Hood turned detective, à la Saint, seemingly escapes from Richard Eliot’s pages; he burgles neighbours, investigates his own crimes, leaves sinister messages, throws bombs, and behaves swinishly, while Eliot’s manuscripts rewrite themselves. Then too there are academics competing for a codex, and arms dealers masquerading as the Friends of the Venerable Bede. There is a young diplomat as circumlocuitously circumspect, as magnificently, wordily bland, as Sir Humphrey (no relation) Appleby; eccentric old ladies born the year Wordsworth died, living in a permanent Victorian twilight; and writers of grimly Hardyan rural novels. And it all hinges on the anatomy of the camel.

The plot is extremely subtle, the reasoning very fine, even abstract (tendentious, the disaffected might say). But the pleasure of Stop Press is less in the detection than in the wit.

“From the point of view of literary texture, of the capacity of the text to sustain repeated rereading with enhancement rather than diminishment of aesthetic pleasure,” George L. Scheper (Michael Innes, 1986) writes, “Stop Press is virtually without parallel in detective fiction. It is a novel proportionally far less dependent than most mysteries on sheer plot – on ingenious crime and ingenious solution – than on the richness and subtlety of the prose and wit of the dialogue for its effects.”

There is the famous description of the dogs, “latrant, mugient, reboatory”. There is a clever structural homage to Pope’s mock-epic The Rape of the Lock, each section of the book beginning with a glorious description of the sun. (See Scheper.) There are metaphysical discussions on writing and the power of words to create, with reference to Swift; on whether vital literary characters like Iago or Mr. Micawber are more real than everyday types we see rarely; and on whether the real world and the world of dreams can collide and cross. There are excursions into morbid psychology: Winter’s explanation of paramnesia casually explains Wordsworth’s natural mysticism, the Platonic theory of reminiscence, and the doctrines of reincarnation. (Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, too, one might surmise.)

There is also the Shoon Collection, one of the finest of all libraries in detective fiction – here is the whole of Shakespeare; here are Milton, Cowper, Byron, and Shelley (bought with profits from supplying African labour to central Arabia), Coleridge and Wordsworth – while a guest walks off with Keats’s Poems of 1817 and a first edition of the Rubá’iyàt of Omar Khayyám. (A library of lost works – perhaps in a museum of the lost – would make a splendid setting for a detective story. On the shelves are Homer’s Margites; Suetonius’s Lives of Famous Whores, Physical Defects of Mankind, and Greek Terms of Abuse; and the plays of Agathon, while allghoi khorkhoi slither through the corridors and the emela-ntouka frolics in the swimming pool.)

Stop Press was lauded on both sides of the Atlantic. The Times Literary Supplement declared it “unquestionably the best detective story published for many months”; in America, Saturday Review named it one of the seven best detective stories of 1939. More recently, Julian Symons judged it perhaps Innes’s masterpiece, while Scheper considers it the best country-house mystery ever written.

But Stop Press may be an acquired taste; some readers might very well hate it (particularly those who read little but detective fiction, and who read only for plot). Even the late Wyatt James (“Grobius Shortling”), an Innes enthusiast and a man at home with 18th century literature, detested it. The TLS acknowledged: “It may not be everybody’s cup of taste, for it is leisurely and highbrow.” Barzun and Taylor considered it “immensely entertaining in small doses, but only if one relishes the [Henry] Jamesian prose and the literary or historical parodies and allusions.”

Those who enjoy Stop Press will, however, enjoy it immensely; as high-spirited highbrow comedy, it is not entirely unsuccessful. For my part, I would rather read this than a dozen standard detective stories.

Blurb (US)

William Lyon Phelps crowns Michael Innes “The King of Mystery Writers”

Richard Eliot’s mystery stories always enjoyed a very substantial success. His plots were invariably sound and the Spider, his principal character, pursued his adventures with an engaging nonchalance. The author’s thirty-eighth thriller was well under way when the Spider suddenly came embarrassingly to life and performed a series of increasingly sinister exploits in Mr. Eliot’s own house, exploits which the author had thought of making his character undertake in previous books and then had abandoned.

Michael Innes, who has written so brilliantly in SEVEN SUSPECTS, HAMLET REVENGE! and LAMENT FOR A MAKER, gives us a masterpiece of witty deduction. Conceived with intelligence and a fine sense of the satiric, this new mystery novel has brisk narrative pace and a mounting atmosphere of suspense.

Contemporary reviews

Times Literary Supplement (Maurice Percy Ashley, 4th November 1939): MYSTERIOUS SPIDER

Mr. Michael Innes’s Stop Press is unquestionably the best detective story published for many months. It may not be everybody’s cup of tea, for it is leisurely and highbrow. Moreover some readers may object to nearly 500 pages without even a—but that is unfairly to disclose the plot. Yet for careful, dignified and at the same time unfailingly witty writing it would be hard to beat and the characterisation—with possibly one exception—is admirable.

The exception is Mr. Eliot, the writer of thrillers whose fictitious creation “the Spider” suddenly comes to life and starts playing practical jokes on him. There is always a certain risk of tediousness in detective story writers electing to make their central figures detective story writers and in this case Mr. Eliot is not a sufficiently lively character to disarm the critical. But this is more than compensated for by the other characters, notably two excellent denizens of an Oxford Senior Common Room. One of them is the tutor of Mr. Eliot’s son and at his invitation goes to a house party to try to resolve in an amateur way the mystery of the living Spider. He soon retreats, however, before the presence of a professional, a detective from Scotland Yard who also comes to the party to give the benefit of his sagacious advice in the course of a busman’s holiday.

The novel requires close reading and it may be that the detective resolves his complicated problem by an undue proportion of highly ingenious guesswork. But the problem is not all. The host of entertaining characters, ranging from the dons to an arms manufacturer who carries out his “nefarious” activities through a body known as the Friends of the Venerable Bede are worth the reading alone.

Birmingham Daily Post (7 November 1939): One Puppet Breaks

In his fourth novel, which is a detective tale of sorts, Mr. Michael Innes exploits, with variations of his own, an idea which also attracted (among others) Pirandello and Robert Louis Stevenson: the idea of the imagined literary character coming to independent life. Mr. Richard Eliot was the elderly and wealthy author of a string of thrillers “featuring” The Spider. What, then, is to be made of the matter when (as it would seem) The Spider suddenly develops a meddlesome, vexatious, even (again yn as it would seem) a dangerous personality of his own? The easy explanation – malicious monkeytricks – will not serve. It might account for a queer burglary, for some annoying telephone messages, even for the macabre jest which signalised the close of The Spider’s customary birthday party at Rust Hall; it could not explain the joker’s surprising knowledge projected incidents in his own past career which had never been confided to anybody, or put into print.

So young Appleby, Scotland Yard man and guest in the house, must dispose of all sorts of theories, involving spooks, morbid psychology and what not, before he can declare that “a murder has been arranged” – of whom and by whom even then is uncanny matter for conjecture. Will it in the end be objected that the threads he weaves so craftily together compos a pattern too bewildering by half? Perhaps. His mystery would have been mysterious enough had it related only to somebody’s eagerness to prevent Mr. Eliot from writing more – and excluding all the academic dignitaries from Oxford, and their Codex, and their cattishness, from the scene. Yet that would have been a pity; for it is when the dons are upon the scene, and conversing donnishly, that Mr. Innes is obviously most enjoying himself. They combine with the Bohemians of the birthday party, and with the black sheep of the Eliot family, to give the story a flavour which none but Innes could have imparted.

The Scotsman (20 November 1939): Thriller-Writer Persecuted

Stop Press is Michael Innes’s most ambitious story. That, however, is not to say it is his most successful, and one reader at least would rate Lament for a Maker higher. The problem which Stop Press presents is the identity of the perpetrator of a series of strange events at the home of a litterateur-landowner-thriller-writer who has won affluence from his popular series of “Spider” stories. For the most part these menacing portents which look very like practical jokes take place during the period in which a house-party is celebrating the “Spider’s” majority. To go into the complexities of the plot is beyond the capacity of a brief review; but Appleby, the chief of several investigators, acquits himself with his wonted brilliance; and a most admirable character is Bussenschutt, one of the academic interlopers in the scene, who administers a large proportion of the story’s subtle and charming humour. What chiefly makes this book difficult reading is the preternatural allusiveness of the dialogue, the literary erudition of many of the characters, all too willing to display their virtuosity in conversation.

The Times (2nd January 1940): OXFORD COMMON ROOM

Mr. Michael Innes has produced a book remarkable at least for one thing—it has no murder in it, if we except the death of a pig. Stop Press is an erudite and curious novel, not perhaps for all tastes, but certainly not to be missed by connoisseurs. Richard Eliot, middle-aged author of best-selling crime novels, is the victim of a series of macabre practical jokes which suggest that his central character, “The Spider”, has actually come to life. The story moves between an Oxford College Common Room (drawn with a delightful irony) and Rust Hall, the Eliot home, until, among the sham-Gothic splendours of Shoon Abbey, residence of an armament king, Inspector Appleby unmasks the joker. In the words of Mr. Eliot’s favourite and much quoted author, the book may be summed up as: —

“A mighty maze! but not without a plan.”

A Catalogue of Crime (Barzun & Taylor, 1989): The idea of this long book is that the fictional “Spider” of Richard Eliot’s criminous and other tales comes to life to plague the Eliot family—a collection of eccentrics full of malice and greed. The plot is enormously complex. The conversations are amusing but long-drawn-out (457 pages), and the work of Appleby and his sister, who come in late, is rather nebulous. To sum up: immensely entertaining in small doses, but only if one relishes the Jamesian prose and the literary or historical parodies and allusions.

When reading this review I thought it might be the book to make me give Innes another try. I really do like the idea of the character that can come out of the book and cause chaos. However, the plethora of other plot tropes, which seem less appealing, make me concerned that the premise I like may not get as well handled as I would like.

LikeLike

You might enjoy this, but it should be judged as a literate comedy of manners / interwar clever novel rather than as a detective story. I know you haven’t particularly warmed to Innes; you liked HAZELWOOD, but WEIGHT and LAMENT left you cold. Have you read HAMLET, REVENGE?, PRESIDENT’S LODGING, or SONIA WAYWARD?

LikeLike

I’ve read Death at the President’s Lodgings, There Came Both Mist and Snow, The Crabtree Affair, The Daffodil Affair, An Night of Errors, Appleby on Ararat, What Happened at Hazlewood, Appleby at Allington, Lament for a Maker, From London Far, Lord Mullion’s Secret and The Weight of the Evidence. The only one I particularly liked was Hazlewood.

LikeLike

You’ve read a lot of Innes’s best works. I’d still suggest trying Hamlet, Revenge and The New Sonia Wayward. Maybe The Bloody Wood, too.

LikeLike

I must re-read this, although I doubt if it will replace “Lament for a Maker” as my favourite of his books.

LikeLike

Yes, I prefer LAMENT too, certainly in terms of dazzling plotting and menacing atmosphere.

LikeLike

What a pleasure to read this witty and thorough appraisal of a marvellous book. I particularly relished your praise of Innes’s style, to which most of his modern reviewers don’t pay enough attention. The texture of his writing at its best is exquisitely enjoyable in itself.

LikeLike

Thanks, Daniel!

LikeLike

I have been meaning to go back to Innes for quite some time now but don’t think will (re)start with this. And now I really want to pick up Appleby’s End from my shelves and re-re-re-read it;)

LikeLike

Your review was very informative. It convinced me that I do not have the cultural capital required to savor this work.

LikeLike

Interesting to see this review and the comments – I thought I might be the last person in England to still read Innes. But I have to say that although I’ve read [and reread] a lot of his books, ‘Stop Press’ is the only one I just haven’t been able to get through.

LikeLike